In the teachings of the Buddha, all human suffering is summarized by the three poisons: Greed (Tham), Anger/Hatred (Sân), and Delusion (Si). Just three short words, gentle to pronounce, that a four-year-old can recite. But these are also the very three words that a seventy-year-old who has practiced their whole life may still not be certain they have eliminated. This is the paradox that Buddhism calls the “sublime Dharma” (diệu pháp): the truth is simple, but this very simplicity touches the deepest part of human nature. Where reason is not strong enough to control, and where emotions and instincts operate like an underground stream for millennia.

To understand why the path to liberation sounds easy but is difficult to walk, we need to look through three lenses: the original teachings of the Buddha, modern psychology, and the philosophy of human nature. Simultaneously, we must also explain the current common phenomenon in society: why people often follow famous monks, renowned teachers, or those with strong media presence, yet fail to truly return to learning and practicing according to the Buddha’s words, which are inherently simple and unadorned.

Why is letting go of Greed, Anger, and Delusion so hard that it may not be achieved in a lifetime?

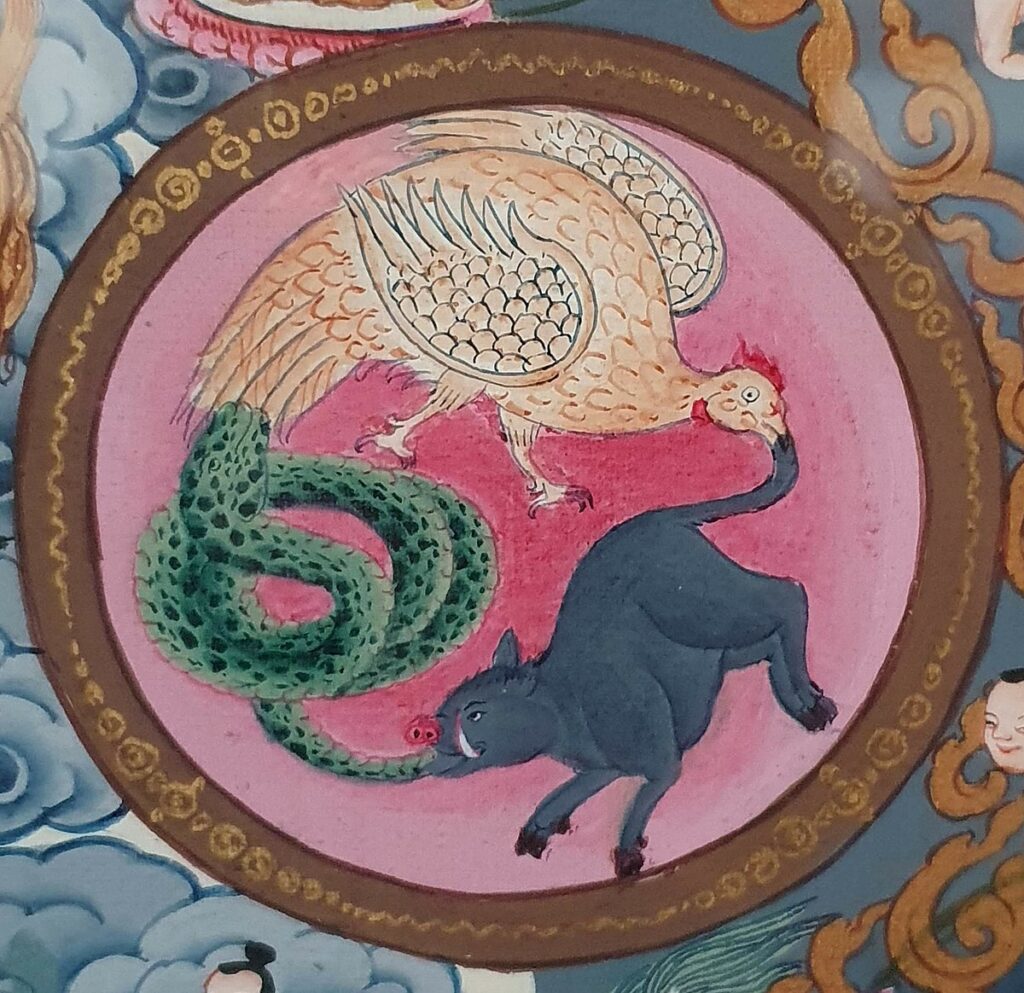

In Buddhism, Greed, Anger, and Delusion are not merely bad habits or moral failings. They are seen as three “energy streams” that constitute the ego. Greed (Tham) is the expression of the desire to maintain and strengthen the self. It makes people want more, want to hold on, want to possess, and want to have more than others. Anger (Sân) is the reaction when the self is threatened, when wishes are not fulfilled, when honor is hurt, or when demands are not met. Delusion (Si) is the most subtle of all; it is the mind’s haziness, the illusions people cling to as truth: imagining the world is fixed, that emotions are real, that the self is the center, that everything can be grasped or controlled. Thus, letting go of the three poisons is not abandoning a few superficial actions, but abandoning what constitutes “I am me.” It is the process of breaking down the shell of the ego, a task which human nature inherently resists.

When the Buddha taught that to escape suffering, one must begin by recognizing and eliminating the three poisons, the teaching sounds very clear. But the practice requires a very long time, sometimes a whole lifetime, because these poisons are deeply rooted in the unconscious. A child might understand it simply as “greed is wanting too much,” but an adult carries decades of psychological habits, automatic emotional reactions, mental scars, and ego constructs. Every time anger arises, people react without realizing it. Every time greed appears, they justify it with countless reasons. Every time delusion operates, they think it is a wise decision. Only through mindfulness practice do they see how they have been led astray by their own nature.

The Psychological Perspective: The Three Poisons as the Brain’s Survival Mechanism

Modern psychology offers a crucial perspective for understanding why letting go of the three poisons is so difficult. The human brain is programmed to prioritize survival. When desired outcomes are achieved, the brain releases dopamine, creating pleasure and driving accumulative behavior, this is the foundation of Greed. When encountering something that threatens the ego or interests, the amygdala triggers the fight or flight response, creating Anger. And Delusion is a product of the brain’s energy-saving mechanism: the brain hates change, hates doubting old beliefs, and hates re-analyzing familiar perceptions. It prefers what is familiar, even if it is a mistake.

Thus, the three poisons are not merely “vices” in a moral sense, but a biological system of the brain. They are natural reactions that ensured survival since primitive times. When the Buddha taught practice to eliminate the three poisons, it meant going against millions of years of brain programming. This is why people know they are greedy but still cannot let go, know anger is wrong but still lose their temper, and know they are deluded but still cling tightly to false beliefs. To master these reactions, one needs to train the ability to observe the mind, recognize emotions, and create a pause between stimulus and response. A practice that meditation and mindfulness have guided for over 2,500 years.

The Philosophical Perspective: Humans are Limited by their own Reason

Western philosophy has long recognized the three poisons in various forms. Plato said humans are always pulled by desire; Aristotle argued that anger is a sign of imbalance in the soul; and Hume asserted that emotions are the true masters of behavior, while reason is merely the “servant.” Kant also saw this limitation: humans know the good but still do not do it, because the root of selfishness always prevails.

Thus, Buddhism, psychology, and philosophy converge on one point: humans are led more by instinct and emotion than by reason. Therefore, letting go of the three poisons is not just a moral act but an inner revolution. We must not only learn new things but also erase what we think we are, the habits we have lived with for decades. That is why abandoning Greed, Anger, and Delusion is simple to understand but as hard as climbing a vertical mountain within oneself.

Why do people prefer following famous monks and teachers rather than returning to the Buddha’s teachings?

Current society shows a peculiar phenomenon: people like to listen to Dharma talks from famous teachers, enjoy reading books by those promoted by the media, and prefer lectures with warm voices, flowery language, and beautiful imagery. But most of them do not truly step into the core of the Buddha’s words. The Buddha taught in very simple and direct language: “Greed leads to suffering,” “Anger burns oneself,” “Delusion is the root of the cycle of rebirth,” “Be a lamp unto yourselves.” These words do not pander to the ego, are not entertaining, and do not create a sense of excitement. They force us to look directly at ourselves, something few people enjoy.

People prefer to seek a “representative” rather than practicing themselves. They want someone to inspire them, someone to speak for them, someone to help them feel better about themselves. A good lecture moves the listener, but emotion is not transformation. Many people prefer the feeling of listening to a lecture over the task of sitting in silent meditation for 15 minutes to face themselves. Listening to a famous teacher is much easier than seeing one’s own anger when insulted, one’s own greed when gaining an advantage, and one’s own delusion when veiled by prejudice.

There is another psychological factor: people like what is solemn, appears sacred, and possesses the aura of fame. This creates the “guru effect,” making them more likely to trust influential people than the very simple words in the scriptures. They believe in the teacher’s specialness, rather than the ordinary but correct nature of the Dharma. But the Buddha never taught worshiping him. He only said, “I am a pointer. Whether you walk the path or not is up to you.” However, humans often choose the easy path, following someone, over the right path, which is self-training the inner mind.

This deviation sometimes stems from a lack of doctrinal foundation. People who do not study the scriptures are often drawn to external appearances: a good voice, a dignified posture, beautiful images on social media. But the Dharma is not in the form; the Dharma is in inner transformation. A true practitioner does not practice to look good in the eyes of others, but must clearly see their own mind moment by moment. It is not about listening to many lectures, but truly knowing when greed is present, when anger is present, and when delusion is present. The Buddha’s words need to be practiced, not consumed as spiritual content.

Why is letting go of Greed, Anger, and Delusion the biggest battle of a lifetime?

Letting go of the three poisons is letting go of the ego. The ego always wants to be nourished, to be right, to be praised, to be recognized, and to possess. When challenged, it reacts strongly to protect itself. One can defeat others, but it is very difficult to defeat oneself because the self has the strongest arguments to convince itself that “I am right,” “I need this,” “I am not wrong.” That is why an angry person easily believes they are hot-tempered because they were provoked, a greedy person believes they are just “striving for the future,” and a deluded person believes they are completely clear-headed. The ego protects itself with thousands of layers of justification.

Furthermore, the three poisons do not only operate individually but are also nourished by society. The consumer environment makes people think that the more they possess, the happier they are. The competitive environment makes people more prone to anger, more likely to feel threatened. The chaotic information environment thickens delusion, as people can no longer distinguish between real and fake. Therefore, practicing to let go of the three poisons is not just about looking into one’s own mind, but also about going against the societal current.

The Real Path to Reduce the Three Poisons, No Miracles, Just Training

The Buddha never promised that anyone who listened to his discourse would be freed from suffering. He only pointed out the path; the walking is up to each individual. Letting go of Greed, Anger, and Delusion requires no complex rituals, nor the protection of deities; it only requires mindfulness/wakefulness. When the inner mind brightens, the root of suffering falls away naturally. A mindful person will see greed the moment it arises, and in that seeing, greed weakens. A wakeful person will feel the urge of anger the moment it surges, and with correct recognition, the anger loses its power. An observant person will see the mind’s illusions, prejudices, and thoughts flowing like a stream, and in that clear seeing, delusion begins to dissolve.

This process is not achieved in a day or two. It is like wiping dust off the mirror of the mind; the longer the dust has accumulated, the longer the wiping takes. But a little bit each day, the mind becomes a little brighter. The important thing is not to eliminate all three poisons, but to limit their influence, so they no longer control actions, no longer cause suffering.

The Journey of Letting Go of Greed, Anger, and Delusion is as beautiful as a song

The journey of letting go of Greed, Anger, and Delusion is beautiful like a song, simple like an original truth, yet as difficult as climbing a mountain without seeing the summit. The reason is that the three poisons lie not only in external behavior but in the structure of the mind, the biological mechanism of the brain, and the philosophical nature of humanity. Buddhism does not judge people for having greed, anger, and delusion; the Buddha merely pointed out that they are the cause of suffering and that everyone can change if they know how to practice correctly.

The fact that people follow famous monks and inspirational figures is not because they do not want to practice, but because they are seeking an easier path. But the true path always lies in the Buddha’s words—simple, truthful, unadorned, and needing no one’s validation. Just one moment of mindfulness/wakefulness, and a person will see how much greed they are carrying, how much anger they are burning themselves with, and how much delusion they are living in. And precisely in that moment, the path to liberation begins.

ARTICLES IN THE SAME CATEGORY

Greed, Gold, and the Spiral of Instability in Human History

Karma in Vietnamese Classical Thought and Lessons from Cambodia Today

Words and the Fortunes of a Lifetime: Why a Few Right Sentences Are Enough for an Entire Life

MAGA and the Power Doctrine of Unpredictability: Why Donald Trump Turned Uncertainty into America’s Strategic Advantage

Xi Jinping’s 2026 Bính Ngọ Year: A Pivotal Test of Power in a Water–Fire Confrontation

Latin America’s New Risk Cycle: Why Venezuela is the “Strategic Anchor”

ARTICLES IN THE SAME GENRE

Karma in Vietnamese Classical Thought and Lessons from Cambodia Today

Religious Faith: Good, Evil, and the Journey from Enlightenment to Fanaticism

What to Note about “Apocalypse,” “Degenerate Dharma,” and Prophetic Culture

TODAY’S CHARITY: THE BRIGHT SIDE, THE DARK SIDE, AND THE ROOT CAUSES.

The Buddha’s Teachings on Generosity (Dāna): Wholesome Deeds, A Kind Heart, and the Confused Context of the Dharma-Ending Age

Buy Virtue